The State of the Video Codec Market 2025

As much as we love debating the pros and cons of new codecs like AV1, VVC, and LCEVC, independent premium-content publishers have largely ignored them. Take Alliance for Open Media (AOMedia) founding members Meta, YouTube, and Netflix out of the AV1 picture, and you’ll hear crickets. Ditto for VVC; other than VVC patent owners like Kwai, ByteDance, and Tencent, which are streaming VVC for software playback on mobile devices, there are few, if any, VVC-encoded streams out there.

Why is this? With AV1 finalised in 2018 and VVC in 2020, why is there such a long delay between the completion of standards and their actual implementation? The simple answer is that increased efficiency (which all new codecs promise) isn’t enough. Codec adoption is driven by business realities: hardware support, market incentives, and clear economic benefits.

HEVC rode the 4K/HDR wave to success, but AV1, VVC, and LCEVC lack an equivalent killer app. With CDNs racing to the bottom on pricing and new royalty pools threatening to increase costs, codec adoption is no longer just about technical merit—it’s about survival. These are the issues I’ll explore in this article.

WHY ADOPT A NEW CODEC IN THE FIRST PLACE?

Virtually all streaming producers support H.264 because it offers as close to universal compatibility as possible. It simply plays everywhere. There are two reasons to adopt another codec besides H.264: bandwidth savings or to enter a new market.

Regarding bandwidth savings, I last tested codec efficiency in June 2023, when I produced the numbers shown in Figure 1. No one will agree with every number, which probably understates AV1’s advantage over HEVC and definitely understates VVC’s advantage over AV1. But you get the point: Advanced codecs can deliver the same quality at lower bandwidths.

Figure 1. Approximate savings delivered by advanced codecs

There are a few realities worth noting about the percentages shown in Figure 1. First, you’ll realise those savings only when streaming to compatible platforms, which will be well short of 100% of the time. Second, you’ll realise those savings only at the top rung of your encoding ladder—which, in fairness, is typically the most widely viewed rung. However, if you distribute lots of middle-rung content to mobile devices, you’ll be swapping a 2Mbps H.264 rung for a 2Mbps AV1 rung. The video should look better, improving the QoE for your viewers, but you’ll see no bandwidth savings.

In addition, as bandwidth costs drop, the savings drop as well. Twenty years ago, when it cost $0.50 to deliver a GB of video, a 50% savings was substantial. Today, BlazingCDN offers low-volume pricing starting at around $0.005/GB, making the bandwidth savings worth 100 times less today.

Beyond reduced savings, most codec proponents ignore the cost side of the equation. Before deploying a new codec, you have significant testing costs; if you have your own encoding pipeline, you have integration and testing costs. After deployment, you have the additional transcoding costs since you typically can’t drop one codec because you’re adopting another. The costs are all additive. You also have additional storage costs for the transcoded files and decreased caching efficiency at the edge because you may have to cache multiple versions of the encoded file for full coverage.

It’s easy to look at Figure 1 and ask, “Why not adopt AV1? You’ll save 38% of your bandwidth costs over HEVC and 59% over H.264.” The numbers are not quite that simple.

This isn’t to say that bandwidth savings don’t matter, but the incentive is nowhere near what it used to be. That leaves one other major reason to adopt a new codec: entering a new market.

THE NON-REPEATABLE EXPERIENCE OF HEVC ADOPTION

Regarding new markets, the only relevant one in the last 12 years or so has been 4K/HDR. You need a 10-bit codec for HDR and encoding efficiency for 4K, which is why HEVC quickly supplanted H.264 for the 4K/HDR market. All codecs launched after HEVC also support HDR and efficient 4K delivery, but if you’re already producing HEVC, the incentive to add another HDR-capable format is much less. This is why AV1, LCEVC, and VVC didn’t share the near-instant adoption enjoyed by HEVC.

It’s worth reflecting on that. Looking back, the surge of demand for 4K HDR content, combined with the ability to deliver it via streaming, created a rising tide that quickly floated technology boats like HEVC and Dolby Vision. Normal consumer upgrade cycles don’t apply when your neighbor/brother-in-law/girlfriend has one of those ultra-cool big-screen TVs with amazing color and contrast. It’s tough to go back and reconstruct the exact timeline, but the HEVC spec was finalised in January 2013, and TVs supporting 4K HDR started appearing in 2015. There were 4K TVs before then, but these appear to have been built for displaying H.264 content.

The first HEVC patent pool from MPEG LA (now Via LA) didn’t launch until September 2014, while the seismic HEVC Advance launch was in March 2015. By then, the must-have nature of 4K/HDR assured HEVC’s success.

So, if the die was cast for HEVC within 2 years, why has adoption proven so much slower for AV1, VVC, and LCEVC? Only the largest streaming shops like YouTube, Meta, and Netflix seem to adopt new codecs for bandwidth savings or QoE improvements; most other producers adopt new codecs only to enter new markets. And there have been no new markets.

WHAT ABOUT PUBLISHER SENTIMENT?

Figure 2 shows the codec utilisation graph from “The 8th Annual Bitmovin Video Developer Report” (2024–2025) for VOD and live combined. Respondents are from the entire streaming media ecosystem, not just publishers, with bars depicting the number currently supporting the codec and the number that plan to add support within 12 months in red. In previous reports, Bitmovin split the data between live and VOD; this time, it’s combined.

Figure 2. Codec utilisation table from “The 8th Annual Bitmovin Video Developer Report”

Some numbers don’t make sense (21% don’t support H.264?), and others are clearly over-optimistic. In “The 7th Annual Bitmovin Video Developer Report” (2023–2024), for VOD encoding, 8% of respondents said they supported AV1, while 32% anticipated support within 12 months. Since AV1 was 13% in the current report, that clearly didn’t happen.

Still, the new report adds some useful sentiment about which codecs are trending upward and which aren’t. Respondents are still bullish on AV1 and believe HEVC still has room to grow. Anticipated support for VVC was about the same as in 2023–2024, while the sentiment for LCEVC dropped from a combined 10% for VOD and live in 2023–2024 to 5%.

WHAT’S COMING

That’s the background. Now, I’ll explore the progress of VVC, AV1, and LCEVC. I won’t cover Essential Video Coding (EVC) other than to say it’s made little progress to date, and it’s unlikely that you’ll need it on your radar screen in 2025 or 2026. I won’t spend much time on HEVC or H.264; little has changed there either.

Then, I’ll preview H.267, describe different standards for Video Coding for Machines, and discuss what’s happening in AI codecs. I’ll conclude with a look at the codec IP picture.

UP-AND-COMING CODECS

When it comes to codecs, remember that building an ecosystem is like preparing a garden, which entails fertilising the soil, planting seeds, and tending to the sprouts. Until something actually grows (for codecs, this means publisher deployments), it’s impossible to know how successful the garden will be and impossible to predict when it will bear fruit.

When considering the ecosystem, the most vital component is playback. Publishers shouldn’t consider a new codec until it presents a critical mass of available players to justify the expense and start to realise the bandwidth savings. All of the other codec-related data, like comparative efficiency, inclusion in standards, and the availability of encoders, is just noise. Without question, substantial relevant gaps in playback availability are the single most crucial factor delaying codec utilisation.

By relevant, I mean this: Did the inability to play HEVC in any browser other than Safari until 2022 significantly delay HEVC’s adoption by premium content producers? Absolutely not; that battle was won and lost in the living room, and as discussed, HEVC was the clear winner before AV1 was even launched.

VVC

While the VVC ecosystem made progress in 2024, the closest we saw to an actual deployment was a technology demo from Globo, a commercial TV network in Latin America, which conducted a showcase during the 2024 Paris Olympics that utilised VVC and VVC enhanced with MPEG-5 LCEVC. While not a full-fledged deployment, this demo enabled Globo to demonstrate VVC’s potential in a real-world broadcasting environment, delivering UHD 2160p video at 10Mbps.

Why didn’t we see publisher adoption in 2024? VVC didn’t play anywhere then and largely still doesn’t, although there has been some activity of note. In 2024, MediaTek announced the Pentonic 800 SoC with VVC decoding, which the company stated should be in TVs in 2025. The Hantro VC9800D also appeared on the scene, although the announcement date isn’t clear.

Looking at TVs, while Philips shipped several LED TVs using MediaTek chips with VVC playback, none of the articles about those TVs mentioned VVC playback. It’s possible that Philips didn’t enable the feature to save on royalties or other VVC-related costs since, at least in 2024, there was no VVC content to play.

Otherwise, Intel’s Lunar Lake chips for “AI PCs,” released in September 2024, were the first to include VVC decoding capabilities. This is a positive step, but obviously, it will take some time before VVC decoding becomes widespread in computers. As far as I could tell, there were no mobile devices with hardware VVC support at the time of this writing in early 2025. While software companies like Kwai, ByteDance, and Tencent—all VVC IP owners—demonstrated efficient software-only VVC playback on mobile devices in 2022, there were no significant updates on their progress in 2024, and there was news of other publishers distributing VVC for software-only playback.

Notably, in 2024, Amazon acquired MX Player, one of the few publishers to deploy VVC, although this was likely more to accelerate Prime’s penetration of the Indian market than anything VVC-related. In general, as we saw with AV1, although many codec stakeholders advocate for software playback on mobile when hardware doesn’t exist and deploy it themselves, most independent publishers tend to avoid deploying new codecs to mobile until hardware playback is available.

The VVC encoding ecosystem has seen development in encoders, transcoders, players, and standardisation. Fraunhofer’s VVenC is an open source H.266/VVC encoder that has seen continuous development, and MainConcept offers the live VVC encoder used by Globo in the Paris Olympics trials mentioned earlier.

Despite these advancements and the 50% bandwidth savings offered by VVC over HEVC, 4 years after VVC was finalised, there are no major publisher deployments. This is hardly a surprise, since VVC playback is still new and there are no new killer apps driving adoption. While there may be some closed-loop VVC deployments in the near term in which the service controls both encode and decode, VVC for general-purpose streaming remains years away.

AV1

AV1, much like VVC, has seen its share of ecosystem development, but other than AOMedia stalwarts like YouTube, Netflix, and Meta, deployments are few. According to Wikipedia, in July 2024, DMM.com became the first major Japanese company to implement AV1, focusing on anime content. However, the link supplied to verify the claim returned a 502 error (currently unable to handle this request). Scanning the AOMedia press release page revealed that Bloomberg was the only publisher to join the organisation in 2024, and outside of this, I found no news of other publishers adopting AV1 in 2024.

Most other news around AV1 in 2024 was AOMedia-related. Meta integrated AV1 into Messenger, Instagram, and WhatsApp to enhance video quality for real-time communication under low-bandwidth conditions. Netflix reported that AV1 has delivered tangible qualitative benefits for its streaming service and was the second-most-streamed format on Netflix. Early in 2025, Mozilla began defaulting to AV1 for all WebRTC calls.

Meanwhile, most mid- to high-end smart TVs ship with AV1 support today, and AV1 boasts HDR playback via HDR10+ and Dolby Vision. The installed base of AV1-capable smart TVs is unknown, although it likely hovers around 50%. AV1 browser support remains near-universal, solidifying its position in desktop and web-based applications.

In September 2023, Apple shipped the iPhone 15 Pro and Pro Max with AV1 hardware decode, although in mid-2024, less than 10% of all mobile devices offered it. While AOMedia members like Meta, Netflix, and Google have been aggressive with AV1 software decoders, most independent publishers seem to be waiting for hardware.

Clearly, encoding and transcoding availability isn’t the issue. AV1’s ecosystem boasts various software encoders, such as Bitmovin, AWS Elemental MediaConvert, Telestream Cloud, and HandBrake. AMD’s MA35D, released in late 2024, offers ASIC-based hardware AV1 transcoding, providing an alternative to NETINT’s Quadra and several GPU-based transcoders for high-volume AV1 transcoding. That said, a report from Moscow State University evaluated AV1 transcoders from NETINT, NVIDIA, and AMD and found the output quality of all of them to be behind the highest-performing HEVC transcoder. So, if you plan to deploy live AV1 transcoding, you should evaluate transcoded output quality to gauge the savings this approach will deliver.

Projecting AV1’s future is challenging. The largest user-generated content sites, YouTube and Meta, already employ it, as does the largest premium content producer, Netflix. Most high-volume premium content producers already support HEVC for 4K/HDR, and while AV1’s living room penetration is getting interesting, mobile penetration with hardware playback is still lagging. Overall, browser playback represents a very low percentage of premium content streams. While you would expect larger premium content producers like Hulu and Disney to adopt AV1 at some point, this hasn’t happened.

LCEVC

LCEVC is an enhancement codec that sits above base layer codecs like H.264, HEVC, or AV1 and provides an enhancement layer delivering higher resolutions at lower bandwidths than the base layer codec could deliver the same resolution natively. For example, an LCEVC stream might have a base layer of HEVC at 360p and an LCEVC enhancement layer that takes the file to 1080p.

The benefit of LCEVC is that the combined bandwidth of the hybrid stream is much lower than a native HEVC 1080p stream at the same quality. In addition, the hybrid stream is backward compatible, so any HEVC-compatible player can play the 360p stream, although the enhancement layer requires an LCEVC-capable player. Unlike VVC or AV1, LCEVC is a lightweight codec that doesn’t need hardware to play on mobile devices and can be upgraded via software, avoiding the hardware compatibility issues that have delayed VVC and AV1.

This unique approach offers advantages in terms of compatibility and efficiency, but its adoption in 2024 remained limited. As mentioned, Globo, the largest commercial TV network in Latin America, conducted a TV 3.0 showcase during the 2024 Paris Olympics utilising VVC enhanced with MPEG-5 LCEVC.

V-Nova, the developer of LCEVC, has garnered widespread ecosystem support around the industry. V-Nova’s LCEVC SDK includes a decoder integration layer (DIL) that facilitates integration into various players across different platforms, including Android, iOS, Windows, macOS, and HTML5 players like THEOplayer. V-Nova also offers an LCEVC NDK for integrating LCEVC decoding directly into chipsets used in TVs and set-top boxes.

While LCEVC has shown promise in enhancing existing codecs and has a much clearer royalty picture than any of the other codecs discussed, its adoption remains limited. The Globo Olympics showcase was a significant step that hopefully will soon be followed by true rollouts by mainstream publishers.

HEVC AND H.264

HEVC maintained its position as the leading video codec for 4K and HDR in 2024, largely due to its existing widespread adoption and mature ecosystem. The sentiment shown for HEVC adoption in the new Bitmovin report was impressive, seemingly indicating that HEVC is still on the way up, not the way down.

The same can’t be said for H.264, which is stagnant at this point, although it’s likely the primary, if not sole, codec for most websites that don’t distribute premium content or 4K video. Interestingly, although you might think that H.264, which was finalised in 2003, was coming off patent, Via-LA’s FAQ page shows the pool extending from 2017 and beyond under the same terms and cap ($9.75 million annually). However, while the Via-LA pool does charge royalties for subscription and pay-per-view content, there are no royalties for free internet video, and H.264 isn’t included in either of the content pools discussed later.

H.267

H.267 should be finalised between July and October 2028. If history holds, this means it won’t see meaningful deployment until 2034–2036. According to the JVET’s July 14, 2024, document, “Proposed Timeline and Requirements for the Next-Generation Video Coding Standard,” H.267 aims to achieve at least a 40% bitrate reduction compared to VVC (Main 10) for 4K and higher resolutions while maintaining similar subjective quality.

As shown in Figure 3, H.267’s Enhanced Compression Model (ECM) v13 demonstrates more than 25% bitrate savings over VVC in random access configurations, with up to 40% gains for screen content. Subjective evaluations confirm these gains, highlighting robust performance in both expert and naive viewer assessments.

Figure 3. H.267’s compression performance versus VVC’s in terms of luma PSNR in the RA configuration

Here are a few other key points about H.267:

- It is designed for diverse applications, including mobile streaming, live broadcasting, immersive VR/AR, cloud gaming, and AI-generated content.

- It targets efficient real-time decoding and scalable encoder complexity, supporting resolutions up to 8Kx4K and frame rates up to 240 fps

- It emphasises flexible support for stereoscopic 3D, multi-view content, wide color gamut, and high dynamic range.

What’s not to like? As I detail in the Streaming Media article H.267: A Codec for (One Possible) Future, the H.267 creators have ignored the key issues that delay codec adoption, like the need for dedicated decoders and an utterly twisted IP picture. They are also “innovating” on a 25-year-old codec architecture that has long passed the diminishing returns stage while not mandating power consumption levels that would mitigate the environmental impact of streaming. As currently directed, the best thing you can say about H.267 is that it’s likely to be obsoleted by AI-based codecs and rendered irrelevant.

VIDEO CODING FOR MACHINES

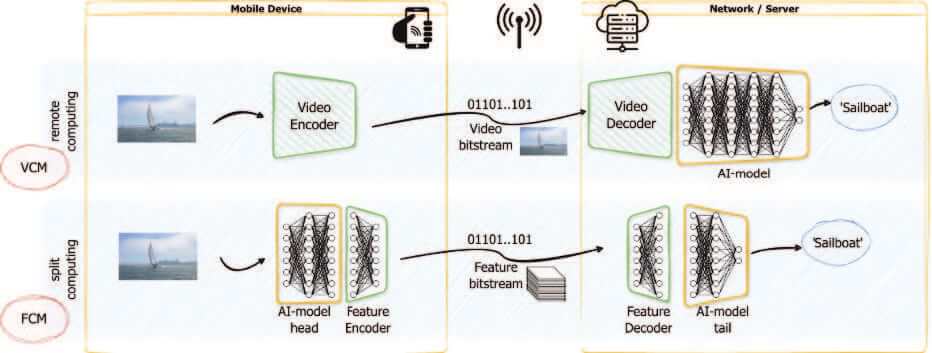

While most videos have traditionally been encoded for human viewers, the proportion of video consumed by machines is on the rise. This shift calls for specialised compression techniques that diverge from those optimised for human perception, focusing instead on accuracy and bandwidth efficiency for machine use. In response, MPEG has proposed two specific standards: MPEG-AI: Video Coding for Machines (VCM) and MPEG-AI: Feature Coding for Machines (FCM).

VCM is tailored for scenarios requiring the transmission of full video streams to remote servers for in-depth processing. As shown on the top in Figure 4, from an excellent article on the InterDigital website, the image depicts a mobile device using a traditional video encoder to send complete video bitstreams for AI analysis at a server, where the information is processed for machine usage. This standard is crucial for applications in which the entire video frame must be analyzed, such as in surveillance and security.

Figure 4. MPEG-AI: Video Coding for Machines and MPEG-AI: Feature Coding for Machines. Source: InterDigital

FCM, however, focuses on encoding and transmitting only essential features of video data needed for machine perception. As shown at the bottom of Figure 4, this method involves an AI-model head on the device processing the video to encode the critical features, which are then transmitted as a reduced feature bitstream to a server for final analysis. This approach drastically cuts down on the volume of data sent over the network, optimising bandwidth for edge-computing environments where processing power is at a premium.

These two approaches represent complementary strategies under the MPEG framework, each addressing distinct aspects of machine-based video consumption.

AI CODECS IN GENERAL

Many traditional codec and encoder developers have used AI to boost the transcoding efficiency of their codecs/encoders, as you can read about in my July 2024 Streaming Media article, AI and Streaming Media. The article also reports that several companies, including Deep Render, are developing entirely new AI codecs. You can read more about Deep Render’s progress here. 2024 saw many new AI-codec-related white papers but no complete end-to-end codec initiatives like that from Deep Render.

PAY TO PLAY

In the May 2024 article titled Decoding the Landscape: Recent Developments in Video Codec Licensing, I discussed historical and ongoing shifts in codec licensing practices, which have shown a clear trajectory toward the imposing royalties on encoded content, including the Avanci Video pool, Broadcom’s suit against Netflix for content royalties, and Nokia’s suit against Amazon for the same. Fast-forward to early 2025, and the landscape continues to evolve with significant new developments.

Most significantly, Access Advance recently launched the Video Distribution Patent (VDP) Pool, a licensing program targeting internet streaming content encoded with the HEVC, VVC, AV1, and VP9 video codecs. The royalty structure features fixed-tiered pricing based on the size of the video distributor’s business, with a six-tier system determined by metrics such as monthly active users, subscribers, and revenue. Licensees pay a single fee covering all four codecs, enabling flexibility in codec selection without additional costs. Specific rates were to be disclosed by March 2025 after further industry consultations.

The program applies to internet video distributors, including subscription-based services, ad-supported platforms, social media sites, and videoconferencing providers. A de minimis exception exists for smaller entities like schools or churches. Organisations with fewer than hundreds of thousands of subscribers or fewer than 1 million active users receive a $25,000 royalty credit per 6-month reporting period, eliminating royalties for small-scale operations.

Looking back at the Avanci Video pool, there’s not a lot known about the cost or structure. I’ve heard that royalties will be charged per codec, but this hasn’t been confirmed. Note that while Avanci Video shows licensees on the webpages for most other pools, there are none shown for the Avanci Video pool when I checked just before press time. If that’s still the case when you’re reading this, it likely means that there are few, if any, licensees.

To encourage early signups, Access Advance is building significant incentives for licensees who join by June 30, 2025. They will have previous royalties waived and will receive a 25% discount through 2030. It will be interesting to see how the pools compete going forward.

The bottom line is that streaming producers are being hit by royalties from patent pools and lawsuits from individual IP owners, while the financial incentive to adopt new codecs is shrinking. There’s no right or wrong here—codec developers need to be paid for their innovations. But the result is real fear, uncertainty, and doubt, not just about codec selection, but about whether adopting a new codec will ultimately be worth the cost and risk. With no clear killer application driving adoption, publishers are left questioning whether adding a new codec is worth the investment at all.

LOOKING AHEAD

As a gauge of my sentiment, my working title for this article was “2024: The Codec Year That Wasn’t.” There are too many codecs with no killer applications, with almost certain royalties on content diluting the diminishing cost savings of adopting new codecs. H.267 seems like a standard designed more with the past in mind than the future, another VVC with a similarly dismal latency between launch and actual utility.

On a bright note, AR/VR applications are coming, and likely a scary and boundless supply of new content from AI sources is coming even if we don’t know when, what, or why. These will all require codecs; the question is if the codecs will be AV1/2, VVC, LCEVC, or H.267 or an AI codec from a completely different source. Time will tell.

Related Articles

In this interview, Jan Ozer speaks with Peter Moller, CEO of Access Advance, and Dylan Zhou, Senior VP of Licensing, about the recently announced royalty structure and initial participants in Access Advance's Video Distribution Patent Pool. The conversation outlines the codecs covered (VP9, AV1, HEVC, VVC), the targeted use cases (video streaming and content distribution), and how the royalty structure is designed to balance fairness and industry adoption.

02 Jul 2025

If you'll be encoding with SVT-AV1 or VVC, in this article you'll learn a bit about how to optimise your encodes, particularly the trade-offs that presets deliver, and how many logical processors to use. With SVT-AV1, I also explore the quality and playback efficiency of the fast decode option, although I didn't find much to show for it. You can also peruse the FFmpeg command strings used for all encodes.

27 May 2025

While innovation is good at the outset of a transformation (such as analog to digital video), it can become counterproductive to building sustainable businesses. Continuous innovation means taking away resources from making existing technologies more scalable, resilient, and reliable—three traits that are critical to the success of something like a streaming platform.

19 May 2025

Transitioning to new codecs in the streaming industry is never an undertaking to be taken lightly, and bandwidth savings, encoding efficiency, and quality enhancements must be carefully considered and balanced against the challenges of ensuring playback capability for the broadest range of viewers who may be operating a motley assortment of legacy devices. Radiant Media Player's Arnaud Leyder and United Cloud's Boban Kasalovic offer their own deployment decision trees for implementing new codecs in this excerpt from a panel discussion with Streaming Learning Center's Jan Ozer at Streaming Media Connect 2025.

29 Apr 2025

All-in-One (AIO) live production devices leverage the latest mobile CPU and GPU power and integrated capability, with real hardware connections for multiple HDMI ports, ethernet, headphones, audio input, and more—all from one manufacturer so there's just one update cycle to track. Magewell recently came out with the 3.0 update to their Director Mini AIO production tablet (Figure 1), and they are pushing the envelope with what these little powerhouses can do.

05 Nov 2024

While VMAF has been a valuable tool for assessing video quality, its limitations highlight the need for complementary metrics or the development of new assessment methods. These new metrics should address VMAF's shortcomings, especially in the context of modern video encoding scenarios that incorporate AI and other advanced techniques. For the best outcomes, a combination of VMAF and other metrics, both full-reference and no-reference, might be necessary to achieve a comprehensive and accurate assessment of video quality in various applications.

05 Nov 2024

It's been 3-plus years since the MPEG codec explosion that brought us VVC, LCEVC, and EVC. Rather than breathlessly trumpet every single-digit quality improvement or design win, I'll quickly get you up-to-speed on quality, playability, and usage of the most commonly utilised video codecs and then explore new codec-related advancements in business and technology.

04 Apr 2024