Buyer's Guide: Portable Capture and Transcoding

This article appears in the February/March issue of Streaming Media magazine, the annual Streaming Media Industry Sourcebook. In these Buyer's Guide articles, we don't claim to cover every product or vendor in a particular category, but rather provide our readers with the information they need to make smart purchasing decisions, sometimes using specific vendors or products as exemplars of those features and services.

Anytime you shoot an event accessible to power and connectivity you should consider streaming it live, which is both simple and inexpensive. To do that, though, you'll need a software program or device to encode the signal and send it to a streaming server. You have two basic choices; dedicated appliances, and software programs.

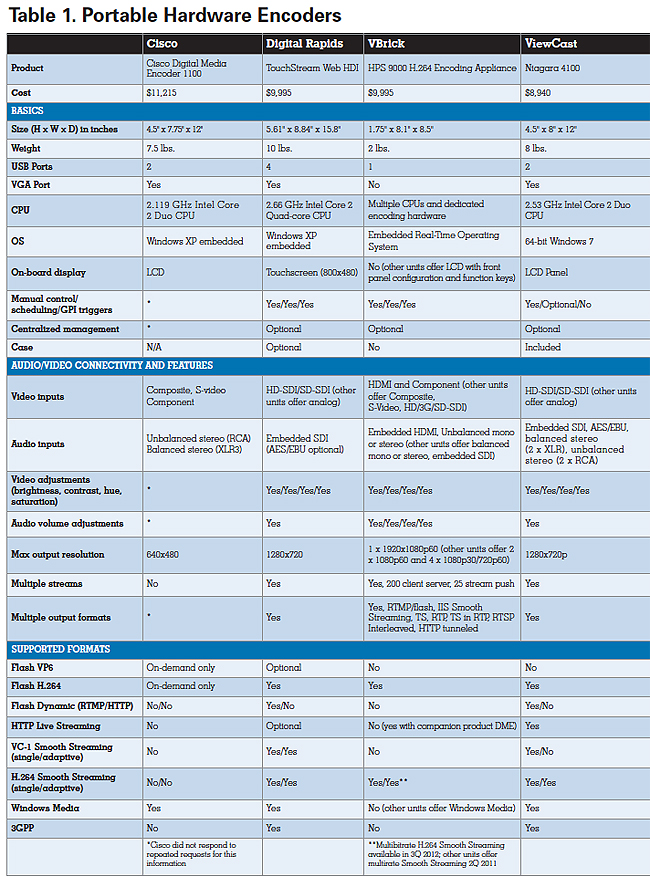

We'll look at both categories in this article, but to set the stage, let's discuss two trends that will impact your selection criteria. Briefly, in the past, when broadcasting live, your on-site encoder created all streams and transmitted them to a streaming server for distribution. (A features table comparing leading portable hardware encoders is at the end of this page; a similar table for software encoders is at the end of page 2.)

For example, If you were streaming live to Flash desktops and HTTP Live Streaming-compatible (HLS) mobile devices, you needed two sets of encoders, or one high-performance encoder capable of producing streams for both formats. If you were streaming adaptively, you needed encoders capable of producing multiple streams, plus the outbound bandwidth required to deliver those streams to the streaming server. These requirements often necessitated multiple encoding systems and strained the outbound bandwidth capabilities many event locations.

Today, two commonly available features of streaming servers reduce these requirements. The first is transmuxing, or the ability to convert the container format and/or distribution protocol of an incoming stream and repurpose it for multiple outputs. For example, most streaming servers today can input a set of adaptive streams encoded for Flash distribution and repurpose it for HLS devices. In addition, Microsoft's Information Internet Server (IIS) can repurpose a Silverlight Stream for HLS output.

The second feature is real-time transcoding, which converts a single input stream into multiple adaptive streams. Two examples are the Wowza Transcoder AddOn and the Haivision HyperStream Live Cloud Transcoding service. This capability dramatically reduces the outbound bandwidth requirements at the event, which is often the most significant production bottleneck, as well as the on-site encoding requirements.

The bottom line is that before choosing an encoder, you should understand the streams required by your streaming server or streaming service provider. Though we list the output formats supported by all encoders in the respective features tables, and whether the device or program can output multiple streams, these features may or may not be relevant depending upon which server or service provider that you use.

Hardware vs. Software

Your first decision is hardware appliance vs. software program. The biggest difference is cost; portable transcoding appliances can cost $10,000 or more, while the Adobe Flash Media Live Encoder is free, and others cost $199 and up.

The advantages of the appliances are ease of use, audio/video connectivity, and stability. Regarding ease of use, you can pre-configure your appliance in the office and hand it off to non-technical users for carrying to the event. So long as they can turn the appliance on and connect the audio/video feeds, they should be good to go. If something goes wrong, you can log in and troubleshoot the device from your office. While software encoders aren't rocket science, none are quite this simple.

In terms of connectivity, the only format most notebooks can handle without an adapter is FireWire. If you're not running DV or HDV gear, you'll need an external adapter that for analog or SDI input, which can cost $1,000 or more.

Regarding stability, though all appliances are essentially Windows computers in a box, they tend to be more stable than notebooks because they're single-purpose devices. Users don't load Microsoft Office, the Adobe Creative Suite, and/or other applications, not to mention the latest shareware or freeware apps and browser add-ins, which promotes stability and consistent performance.

Speaking of performance, don't expect a hardware appliance to have magical powers to output many more streams than a similarly configured notebook. They are just computers, after all, and their performance will be similar to a notebook of similar configuration.

On the other side of the coin, beyond price, the biggest advantage of software encoders is the availability of production-oriented features on some programs, like multiple camera switching, titles and transitions.

Choosing a Hardware Appliance

The first features table shows three appliances from different vendors. These are the most expensive web-oriented models available; if you don't need HD output or high-end connectivity, you can almost certainly find a cheaper model.

Nut and Bolts

Before buying any system, make sure that it connects to your audio/video gear and meets your basic output requirements. So you should:

- Find the model that connects to your current audio/video gear and any planned purchases. This means details like A/V connections and whether your audio inputs are line or microphone powered.

- Find the model that provides the required output format or formats in the required resolution and stream count. As mentioned, start by identifying the requirements of your streaming server or servers, or whether you'll even use a streaming server, since some hardware encoders include a server component. If you'll be serving different target devices with different formats and protocols, be very specific when evaluating products, because capabilities differ significantly here.

Other factors to consider include:

- On-board display. Most units include USB ports and a VGA connector, so you plug-in a keyboard, mouse and monitor and can drive each unit directly, or log-in to each unit via another computer. However, where Cisco and ViewCast provide feedback via an LCD and other gauges, the Digital Rapids TouchStream includes an 800x480 touchscreen for operation and video preview.

- Video and audio adjustments. Some systems enable brightness, contrast, hue and saturation adjustments as well as volume control, which are useful if you can't adjust the camera or audio recording system directly. Some also enable noise gate capabilities with varying levels of automatic gain control.

- Scheduling and GPI triggers. Useful if you need remote control over starting and stopping encoding.

- Connectivity to central control. Useful if you need to coordinate several encoders from a single location via a centralized control system.

Other Factors

Beyond these objective features-table items, hardware appliances vary in terms of ease and output quality. If you can't get a unit in-house for testing, you can assess these via product reviews or comments on community forums. Digital Rapids includes links to TouchStream reviews by myself and Tim Siglin on their TouchStream product page.

Though not directly on point, the ViewCast 4100 uses the same interface as other ViewCast encoders. You can read my review of the Niagara 2120 Live Encoder at http://bit.ly/u17JPd and watch a video that I produced on streaming with the Niagara 2100 at http://bit.ly/uDDQiE.

Related Articles

What to look for when you need to transcode and transrate more than just one format

15 Mar 2012

When it's got to be streamed live, you can't cut corners. Here's a list of questions to ask when selecting a live encoding solution.

15 Mar 2012